Learn The Secret Psychology Of Price

The 5 strategic questions to design optimal price points and promotions

Das Narayandas, Professor at Harvard Business School, recently told me:

Pricing is the moment of truth

100% of your revenues depend on your pricing, no matter what.

By learning about the psychology of pricing, you can leverage this to your advantage, whether on the customer or the supplier side.

After all is said and done, pricing is when the proposition of any product or service is tested against the customers’ willingness to pay. Or, as I prefer to think, the customers’ tolerance to pay.

Paying for something is literally painful, as neuroscience suggests that the areas of the brain associated with loss and sorrow fire up when assessing pricing.

Paying equals parting with something, from a psychology point of view, which is why credit cards have you spend more as you feel the parting less.

How can you address the key pricing-related questions effectively?

Question 1: is it possible to manufacture prices & discounts?

Yes.

Our brain is not capable of making a quantitative pricing assessment in absolute terms: the best it can do is to make a relative assessment in relation to something else.

In some circumstances it can be advantageous to create discounts, even if manufactured, in order to push sales from a psychology point of view.

Let me show you an example:

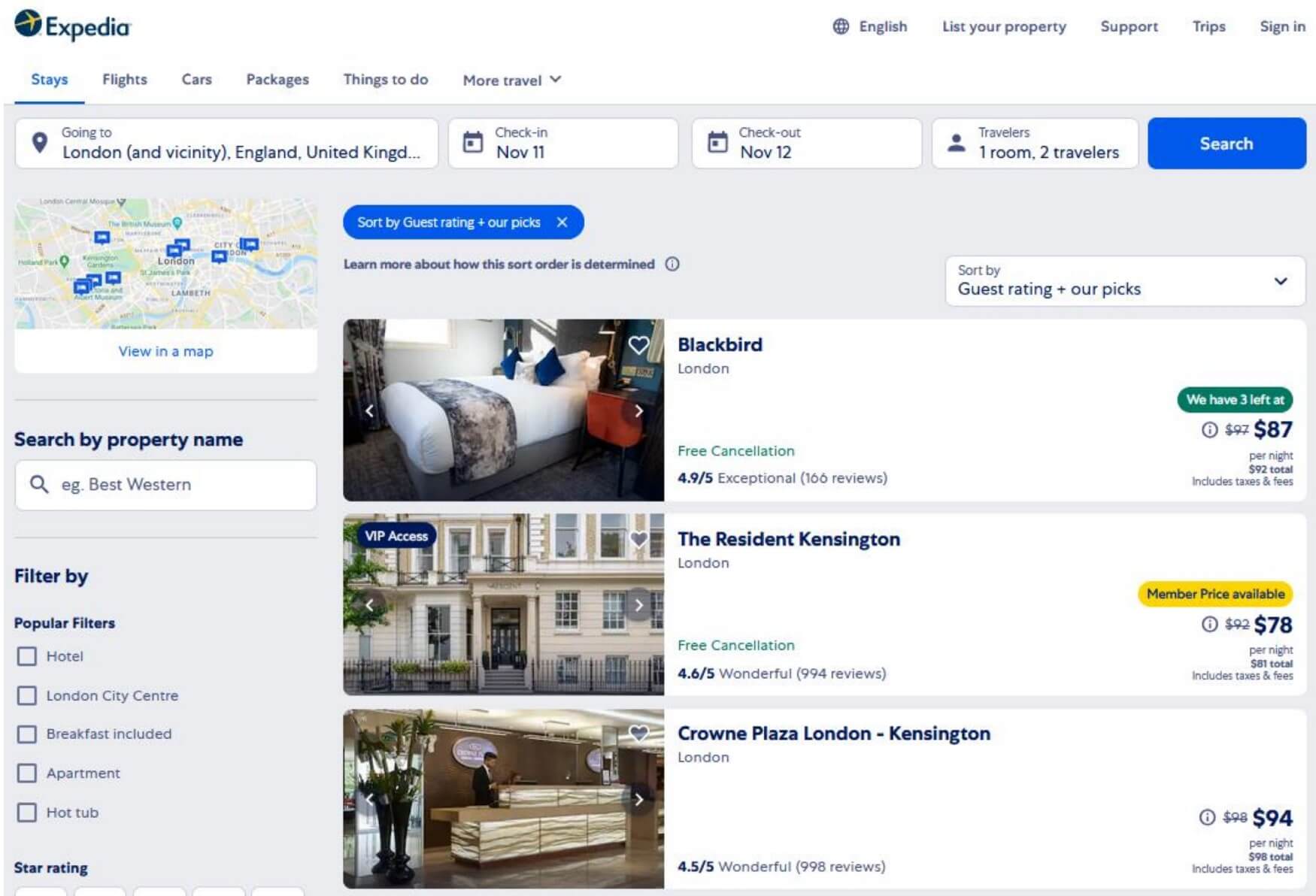

Expedia displays manufactured discounts

Searching for a room in London on expedia.com, image by author (CC with attribution)

Now pay close attention to price merchandising, which means how the price is actually displayed:

$10 off the $97 price: a handy 10% discount? Look twice.

The comparison price is carefully manufactured

Since our brains make the pricing assessment in relative terms, and not absolute terms, displaying the crossed out price helps our brains provide the required reference without struggling to think, in the back-end, about what the actual reference price should be — for example the one you could find on another website, or on a price comparison website like Trivago where potentially you could find a better deal, but at the cost of greater time spent searching and browsing around.

You save time, they make more money: an exchange of value.

This trigger is rooted in the psychology of anchoring (cognitive bias): the classic 1974 experiment of Tversky and Kahneman demonstrated how price perception can even be influenced by using entirely random and unrelated numbers.

Question 2: what is the optimal % discount for customer psychology?

It depends.

Assuming you really have to / want to give away a discount, then you should not only factor in margin and anchoring considerations, but also the impact on customer psychology.

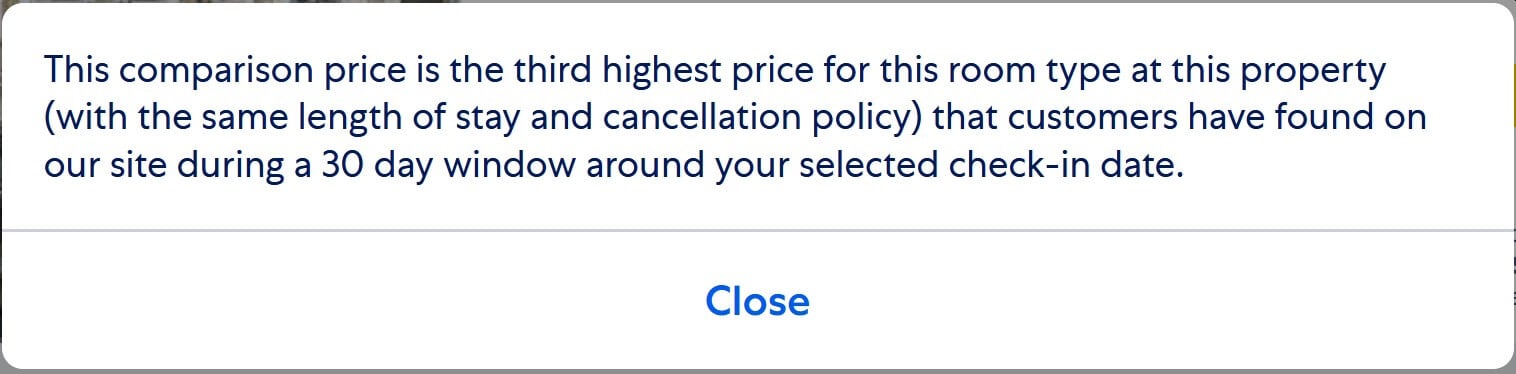

Different discount %ages create different psychological effects

Impact of discount % levels on customer psychology; image by author (CC with attribution)

For example:

- A 5% discount does not carry strong appeal; $10 off sounds comparatively more tangible: in the previous example of a ~10% discount, Expedia is not showing any %ages but rather a crossed out price and a second price point, implying $ off

- A 20% discount sounds reasonable without further explanation

- A 40% discount seems high and requires careful storytelling, to avoid diluting the brand

- A 60% discount undermines the credibility of the full price: if you can provide such a deep discount, why should I EVER want to buy at full price again? Is that even real?

Each context is different, and naturally the guidelines need to be carefully adapted to the specific competitive dynamics of industries, customer segments and regions; but the concept of customer psychology always holds.

Question 3: should you allow any discount?

Offering a discount has obvious advantages:

- Customer perception of grabbing a good deal bargain

- Potentially easier to sell more

- Potentially greater footfall to website / store / salesforce

However, discounting also has some disadvantages:

- Brand erosion, for example reduction in perceived value of the product

- Tactical purchasing, for example forward buying eroding future purchase

- Negative expectation, for example reducing the willingness to buy at full price, permanently destroying profitability.

One thing is sure:

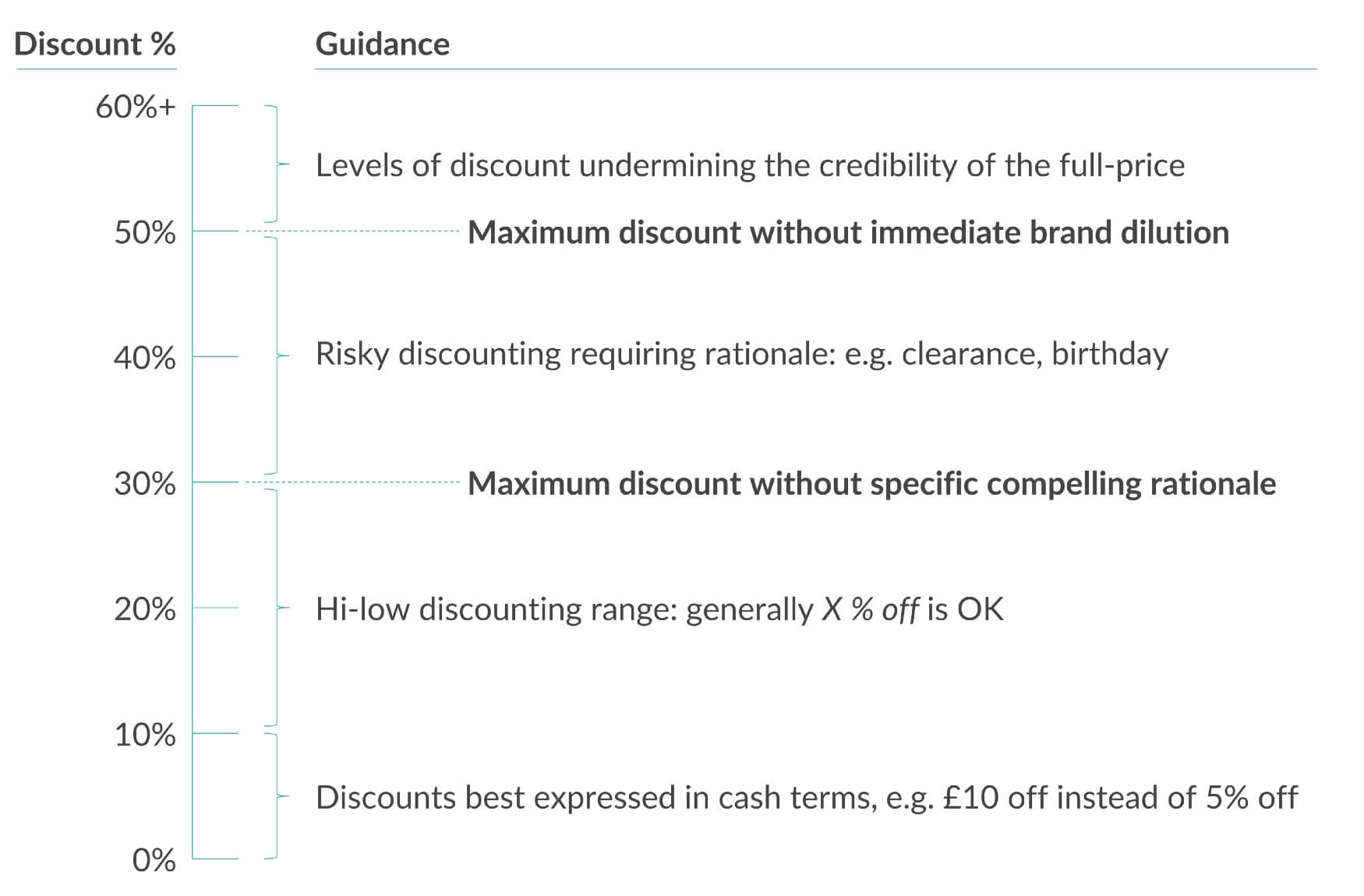

It takes a lot of volume growth to offset the negative margin impact of a discount.

For example, if you sell your product or service at a gross margin of 40%:

- Offering a 5% discount means you need to sell 14% more volume to make the same dollar amount of gross margin

- Offering a 20% discount means you need to sell twice as much

- Offering a 40% discount means you cannot break even no matter how much you sell

This of course also works in reverse:

Increasing the average price by 1% grows the average gross profit by 8%

This due to a simple mathematical property of pricing called margin leverage: since the cost structure remains the same regardless of pricing and discounting, the sensitivity of margin to changes in price is more than proportional.

Giving away a(ny) discount can be very expensive.

Question 4: how high to price?

To determine how high to price a product of service, ask yourself:

Who are you going to sell to? Why are they going to buy?”

An example is worth one thousand words. I will use Business-To-Business B2B examples in this specific section, but the same concepts mutatis mutandis apply also to Business-To-Consumer B2C scenarios, on which I focus elsewhere in this article.

Who are you selling to? The project management platform gitlab.com published a Handbook explaining the rationale of their 4-tier pricing system:

Gitlab.com CEO Handbook: Pricing Model; image by author (CC with attribution)

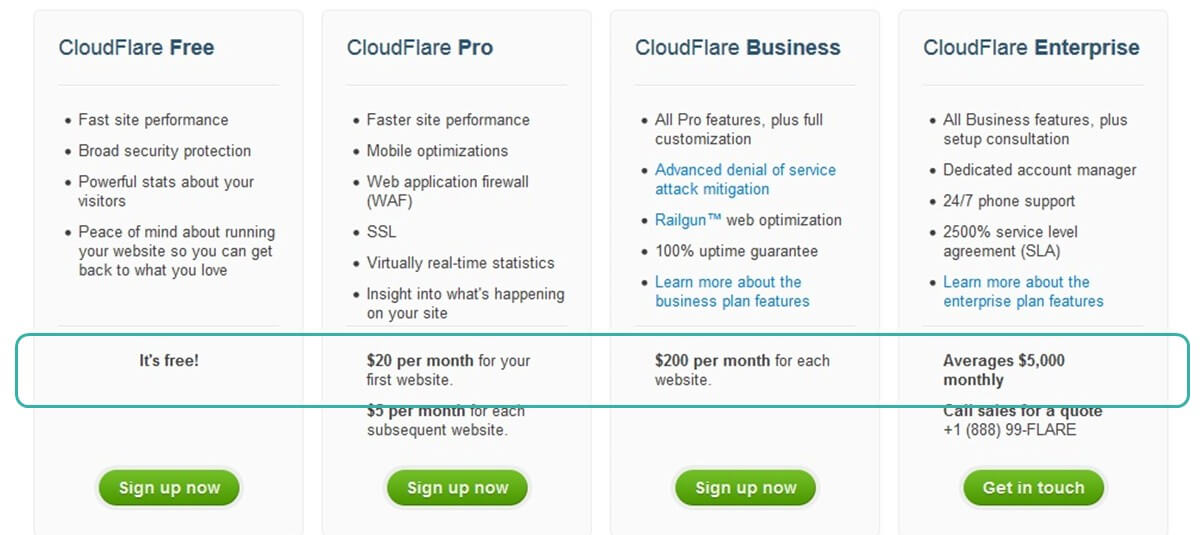

Not uncommon, cloudflare.com also offers a 4-tier pricing system:

Cloudflare.com pricing — look&feel from a few years’ ago, but these pricing levels are still broadly unchanged today; image by author (CC with attribution)

Both these examples show the same product selling at anything literally from 0 to a lot and anything in between, depending on:

- Who is the buyer?

- What exact features do they need the most?

- What is the value to them?

Mind you, the core functionalities of all 4 tiers are broadly the same; however, as Gitlab clearly shows, literally different people do buy different versions of the same product in different ways.

For example:

- The individual contributor may want to test the system or use basic functions without upfront clarity of benefits or purpose, therefore a FREE pricing tier makes sense

- The manager needs certain features for the correct functioning of their business unit, and therefore will be willing to pay a moderate price for the product or service

- The director will want benefits and Return On Investment (ROI) therefore the willingness to pay, so long as the expected benefit is sizeable, will be comparatively higher

- The executive will look for transformation potential, which dramatically alters the performance of a certain part of the business and is therefore key to long-term sustainability = worth a lot.

In terms of number of users, Gitlab suggests:

- Core is for a single developer, with the purchasing decision led by that same person

- Starter is for single team usage, with the purchasing decision led by a team manager

- Premium is for multiple team usage, with the purchasing decision led by one or more Directors

- Ultimate is for strategic organizational usage, with the purchasing decision led by one or more Execs.

Therefore, starting from the question who is buying and why, the definition of value and its fair pricing are more easily addressed than starting from considerations around:

- Product

- Cost

- Competition

Of course these factors are somewhat important, but the buyer is the ultimate judge of value, and not the product or your competition.

NOTE: both examples above do not show any .99 or .95 price endings. These are somewhat effective as the brain scans numbers from left to right and responds better to $199.99 than $200; but you do this at the cost of losing perceived price transparency: in the long-run, we are aware that $199.99 is an optical illusion!

Question 5: how to bring it all together?

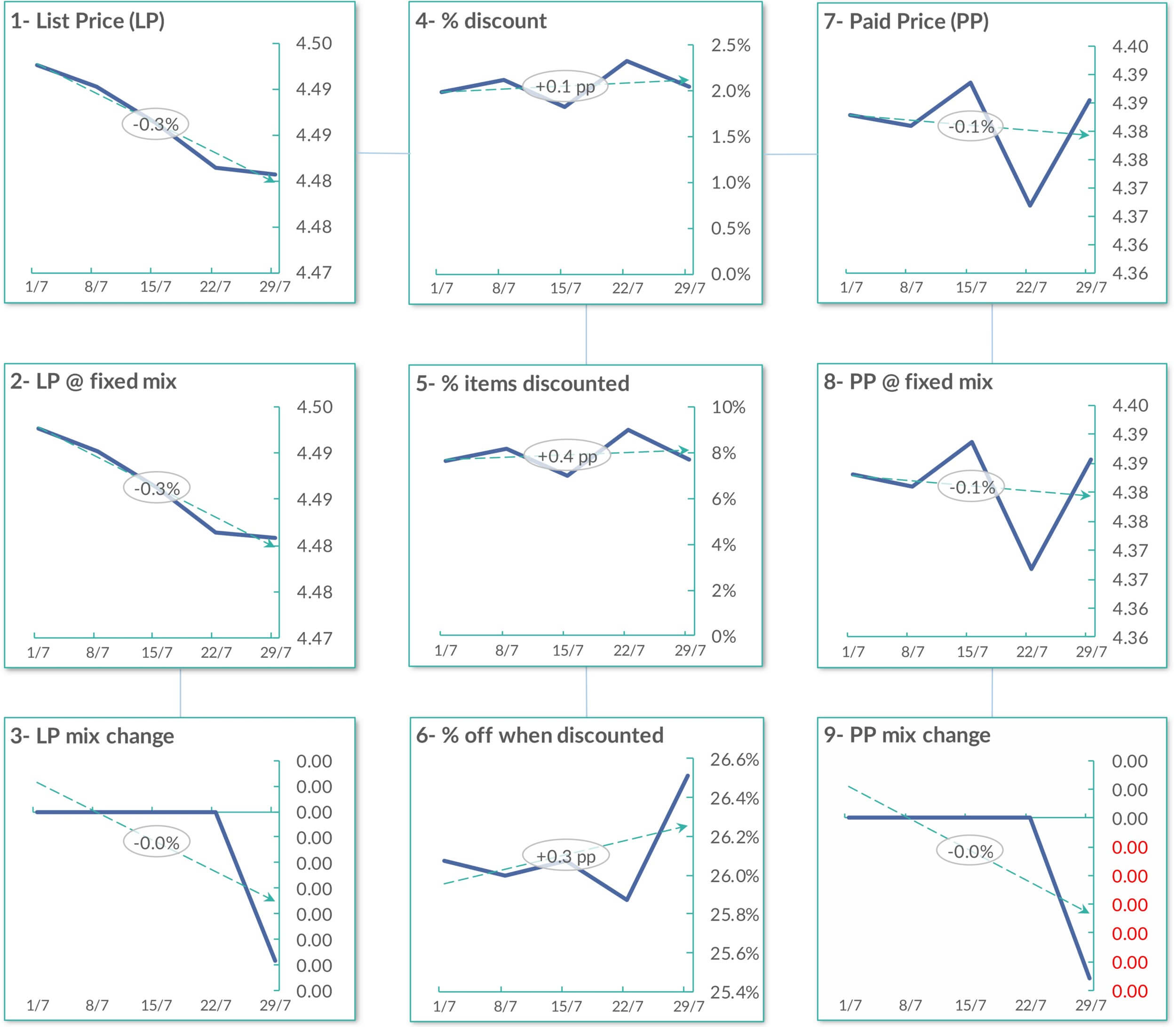

Pricing has 9 components, all intertwined and changing over time. Revenues depend on Paid Price after discounting, and this in turn not only depends on the level of discount, but also the price mix.

Framework: the 9 components of pricing

The main takeaway from thinking about the overall framework should be:

- Promoting a certain category would not only erose its margin, but also grow its sales volume relative to other categories

- So, for example, promoting a cheap category would lower the overall average paid price twice, due to discounting AND due to mix effects

- Therefore, from a managerial point of view, promoting more expensive products tends to promote up-sell, and therefore be relatively less dilutive

Pricing is relative

Pricing is the ultimate benchmark of value. However, the value of anything is never absolute, always relative.

Water can cost anything from 0 in nature to $60,000 for a 750ml bottle for Acqua di Cristallo Tributo a Modigliani and anything in between!

Any dimension of value is relative:

- Product value is perceived in relation to an anchor, therefore seeing an expensive product makes a cheaper product look like a bargain in comparison

- Pricing is relative, for example clever discounting can soften the blow from the psychology of pain associated with paying for something

- The definition of product itself is relative, for example a bottle of water can be functional for the thirsty person, experiential for the restaurant goer, or even artistic for the Acqua di Cristallo drinker!

By learning about the psychology of pricing, you can leverage this relativity to your advantage, whether on the customer or the supplier side.

Happy pricing!

PS I regularly write about Business Science, for example:

How Business Revealed Hidden Pricing Opportunities During Covid-19″

Fashion Is Broken, and Science Is Fixing It”

Monthly summary of Business Science, plus free software and University-level learning launching October 2020:

Free access to the Evo Business Science platform

Any questions? Feel free to connect with me on Linkedin